If you look very closely at the Last Judgment illumination in The Saint John’s Bible, you’ll find a special motif that might just give away the artist’s identity. In the lower right-hand corner of the Dome of Heaven, there is a barely noticeable patch of delphiniums. The average reader might not identify this as a trace of the artist’s hand, but those close to Suzanne Moore certainly will.

“One of the ideas behind gardening,” said Moore, “is that you are creating Heaven on Earth. To me, Paradise must have a garden, and the perfect garden has to include delphiniums.”

Not just any flower would do. It had to be delphiniums, because the very first time Moore planted delphiniums, she was surprised to find 75 remarkably joyful plants sprouted up from her soil.

“They grew higher than I could reach!” said Moore. She was inspired to plant this flower in remembrance of her grandmother Delphina, who she describes as having a magnetic personality and a beautiful open face with white hair.

Moore, an artist for The Saint John’s Bible and the author and creator of a number of artist’s books, has been a gardener for as long as she can remember. Growing up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, her family placed a heavy emphasis on the importance of growing the food one eats.

“We composted in the ‘50s in the middle of the city and grew the vegetables we ate,” said Moore. “I’m a quintessential gardener at heart.”

All that is to say, creation is in Moore’s blood. Though pursuing art and bookmaking was a surprise to Moore herself, who comes “from a family of engineers and architects and inventors, where everybody makes things with their hands,” in hindsight, her career seems pre-ordained.

Moore came up in the art world under the teaching that “art and life and creating your surroundings are all part of one big circle,” according to Moore. This guidance came largely from professors who were trained at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, an art school located just outside of Detroit, Michigan that became a hub for artists who fled Germany during World War II. These mentors instilled in her the idea that to make art is to create something that becomes part of the world, not separate from it.

This is precisely the idea that led Moore to bookmaking.

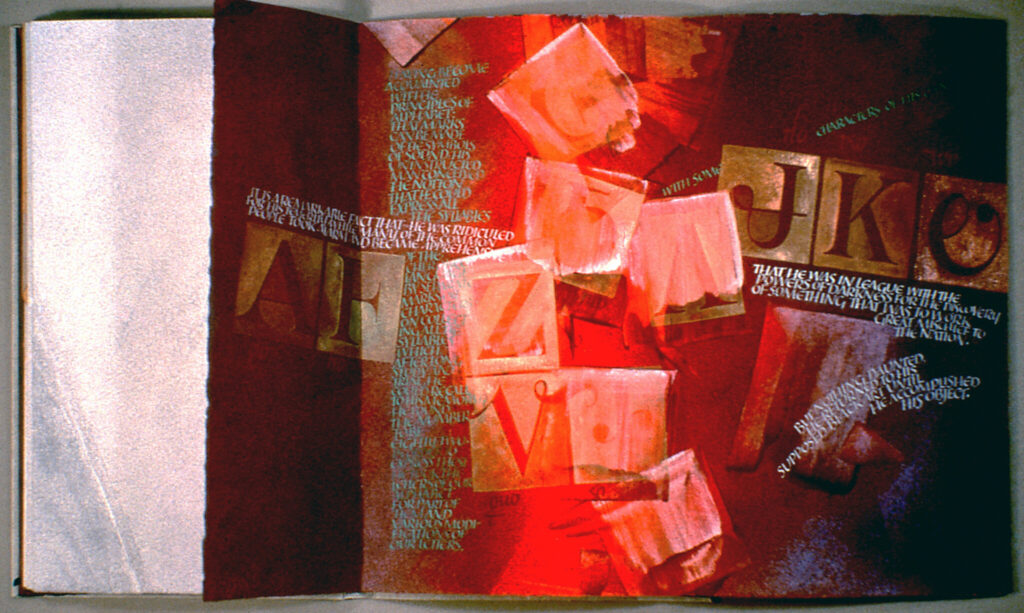

“Books bridge the gap between object and Art (with a capital A) because they are an object that you must hold in your hand,” said Moore. “Your DNA mixes up on the pages with the DNA of everybody else that’s made the book and looked at the book. The intimacy level of this particular art form is really high.”

Moore’s work elevates this experience of intimacy even higher by allowing the interpretive illuminations to live on the page in their full expression. Similar to how the script in The Saint John’s Bible imbues the human touch into the Word of God, Moore’s artful pages imbue emotion and expression into all of her books.

The Word Made Flesh

Moore’s induction as an artist for The Saint John’s Bible came as a personal invitation from Donald Jackson, artistic director of The Saint John’s Bible himself. Moore first encountered Jackson at the first International Calligraphy Conference in 1981 (hosted at Saint John’s University) though the two weren’t yet introduced. It wasn’t until Jackson encountered her work through a mutual friend, Thomas Ingmire, a fellow scribe who was also to become an illuminator on The Saint John’s Bible, that the two officially met.

After twenty years of bookmaking, including four books that told the story of the Cherokee writing system, Moore showed one of the books to Ingmire. Later, he called Moore and asked her to bring her work to a gathering at “our friend Stella Patri’s house.” So, she did.

“Two of my most admired people in my working world, Thomas and Donald, were sitting on the couch looking at this book that I made,” recalled Moore. “One page had a background of brilliant scarlet that went to a deep magenta, with pale green writing on it. Donald looked at me and he said, ‘Whatever possessed you to put pistachio with scarlet?’ I’ll never forget hearing it.”

Moore left the experience feeling proud and full but left it at that. Little did she know, her work had left a mark on Jackson. After twenty years, she answered the phone to his voice. He asked if she would like to work on what would become The Saint John’s Bible, to which she responded, “Why me?”

“Remember that book you showed me?” said Jackson. “I remember how that book felt – and that’s how I want people to react to The Saint John’s Bible. I want people to remember how it feels.”

For Moore, that was the premier compliment she could receive on her art.

“That is the most amazing thing anyone could say about the work that I do,” said Moore. “I mean, if our whole purpose is to share and connect with people, there can’t be anything more satisfying or moving than having someone say, ‘I remember how it felt.’ Not just how it looked.”

A Living Work: St Davids Cathedral Dedication Page

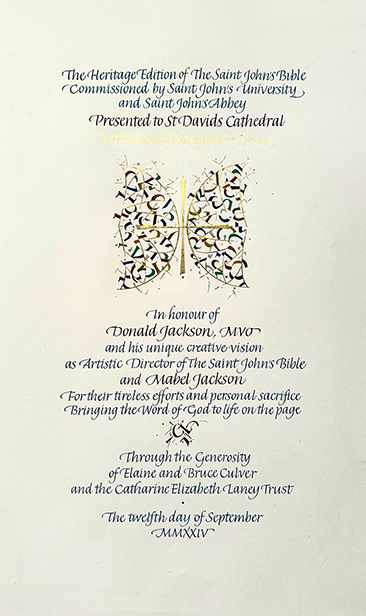

Moore’s involvement with The Saint John’s Bible continues today…long after its final pages were completed. Moore was the artistic mind and hand behind the dedication page for the Heritage Edition gifted to St Davids Cathedral in St Davids, Wales in October 2024. This is the most recent dedication page of the five total that Moore has designed.

Elaine and Bruce Culver, the benefactors of this gift to St Davids, dedicated the edition to Donald Jackson, the artistic director of The Saint John’s Bible and his wife, Mabel Jackson. As such, Moore was invited to craft a dedication page to pay tribute to both the Jacksons and to St Davids Cathedral. To accomplish this, she drew inspiration from the architecture of the Cathedral itself, universal geometric symbols, and the word “visionary,” in honor of Donald.

“For St Davids, because of the concept that the cathedral and the place where people worship is an architectural enclosure, and because I wove various architectural references into my illuminations, I really loved the idea of putting the architecture of that space into the illumination,” said Moore. “So, I used a picture of the vaulted ceiling of the cathedral. I took that design and changed the configuration so that the two halves met in the center to represent Donald and Mabel’s partnership in the project.”

To further emphasize the meeting of minds in the illumination, Moore integrated an equilateral cross.

“The equilateral cross is common to many spiritual traditions all over the world,” said Moore. “Since that was a key concept that we included in the original work, I thought using a more universal cross was perfect. It also helped convey the idea that there’s a center point, and around that the community works with all the different people playing a role in making this vision a reality.”

The symbolism doesn’t stop there. If you look closely, you’ll find that the fragments of color are broken-down versions of the word visionary in five different languages. This is to pay tribute to Jackson, the visionary behind The Saint John’s Bible.

To explore Moore’s expansive and inspiring array of work, view her website here.

The Saint John’s Bible: Made with Human Hands

To read stories similar to this one, visit The Saint John’s Bible Heritage Program blog or subscribe to the e-newsletter Sharing the Word.