June 18, 2011, was a historic day for The Saint John’s Bible—the date that the final crosses were embossed on the page and the work of the Bible’s creators was complete. Now, on the tenth anniversary of that day, members of the Saint John’s community are looking back in reflection on their work to conceive and shape The Saint John’s Bible, share it with audiences around the world, and fulfill its mission to ignite the spiritual imagination.

A “Big Project” for the New Millennium

“At the Abbey we’re always looking for big projects,” says Father Michael Patella, OSB. Fr. Patella cites examples of these “big projects” stretching all the way back to the Abbey’s foundation in the 1800s—the construction of a mill dam to provide power, the first telegraph office at a university, the bold design of the Abbey Church, and the foundation of Minnesota Public Radio, just to name a few. Fr. Patella situates the Abbey’s sponsorship of The Saint John’s Bible among these big projects—the answer to the Abbey’s question of, “What’s next?” in the late 1990s as the new millennium approached.

“If you go through monastic history, it was the monasteries that copied manuscripts and kept information alive,” Fr. Patella says. So as the monks contemplated an undertaking for the new millennium, Fr. Patella says the sentiment became, “How about doing what we’ve always done?” But beyond that, “it meant taking on something we felt that the church and the world needed at that particular moment. It animated us for a great deal of time and really helps define us right now. It keeps us vital,” he says.

Once the Abbey had decided to commission the Bible from Donald Jackson and his team in Wales, that animation and vitality were put to work on the Saint John’s campus via the Committee on Illumination and Text (CIT), chaired by Fr. Patella. The CIT was responsible for selecting the passages to be illuminated and providing direction to Wales. While perhaps less glamorous than the artistry of Jackson’s scriptorium, the CIT’s work was equally crucial, and carried on for an equal amount of time over 12 years.

A Collaboration of Academics and Artists

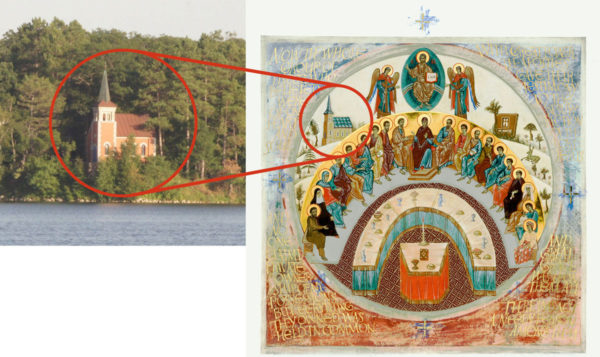

Life in Community, Aidan Hart with contributions from Donald Jackson, Copyright 2002, The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

“Donald Jackson and his artistic team needed input—why are you choosing this passage? How do you see this passage working?,” recalls Fr. Patella. The CIT organized its briefs to Wales with four categories: Exegesis (the meaning of passages according to scriptural research); local associations with Saint John’s or Minnesota; scriptural cross-references; and “free association.” With these detailed briefs, the Saint John’s team was able to guide the creation of art that speaks a universal language, while still incorporating meaningful and specific references to the new Bible’s home and creators.

“We would write it all up and then send it off to Wales, where they would use what we said to broaden their imaginations and decide how they wanted to tackle it artistically,” says Fr. Patella.

Notably, much of this work was conducted in the infancy of email, and the image-heavy communications tested the limits of Saint John’s bandwidth. Fr. Patella recalls that after a crash of the university’s email system in the project’s early days, the teams were forced to collaborate via faxing on color printers.

“The colors were always off,” he remembers. “We’d say, ‘We don’t know what you’re doing with this yellow here,’ and they’d say, ‘That’s not yellow; that’s supposed to be green.’ But as the technology improved, it got better.”

The artistic communication between the CIT and the artists also improved over time. Fr. Patella says, “You had all academics on this side, who are very wordy people. And you had artists on the other side; everything is visual for them. We would write very verbose briefs and Donald Jackson would read them and come back and say, ‘I’m thinking lots of motion and colors!’ He had it all in his mind, but we didn’t know what he was talking about. But then when things got going and we could see the proof in the pudding, we understood.”

Pushing Through to Completion

As the project progressed, roles for additional shepherds became necessary. Tim Ternes joined the University’s Hill Museum and Manuscript Library as its education coordinator in 2003. He soon saw the demand for programming related to the then-unfinished Bible far surpass that for the Museum’s other collections. Ternes helped launch the Bible’s 2005 national tour and worked closely with the Bible’s founding director, Carol Marrin, until her retirement in 2008.

“It was her guidance and her vision and her organizational capabilities that were able to take 23 artists, 12 theologians, 150 monks and 1,400 donors and really move it in a direction to actually get something done,” Ternes says. “So when I took over in 2008, I was able to continue on an unbelievably sound foundation, which was set by Carol. She left big shoes to fill, but I told her I was not going to even try; I was just going to buy a new pair and go from there.”

With Ternes’s direction, the teams on both sides of the Atlantic completed the remaining four volumes over the next three years, with Donald Jackson writing his last letter on May 9, 2011. Ternes and his colleague, Linda Orzechowski, traveled to Wales and held a celebration honoring the artists, presenting each of them with a piece of Richard Bresnahan pottery made from clay from the grounds of Saint John’s.

“We gave each of the artists a piece of Saint John’s because of course we had a piece of their work at Saint John’s,” Ternes says.

“By God, we did this thing.”

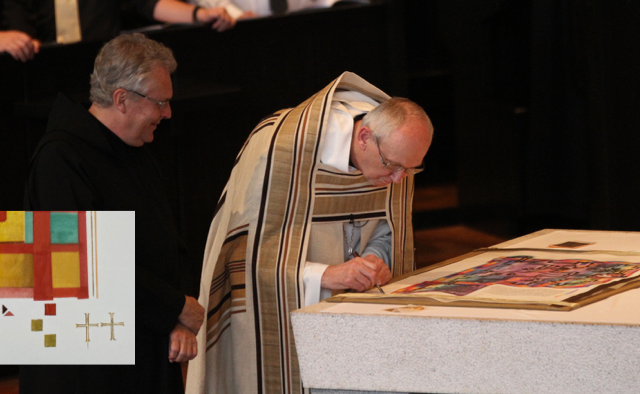

The final ceremony honoring the Bible’s completion was held at Saint John’s Abbey Church on June 18, 2011, during Vespers service.

“We wanted to find a way to bring the Bible home and involve all the people who loved the project—not just donors, but anyone who really was involved in wanting to see it done,” says Ternes.

The Abbey looked to a Jewish tradition to inspire its homecoming event for the new Bible. “When a Torah is commissioned, it is very common for the commissioner to put the last mark of the last word on that Torah,” explains Ternes. “So in keeping with that we decided that we would actually finish the Bible on the altar of the Abbey Church.”

Ternes recalls that approximately 500 guests watched as Donald and Mabel Jackson, accompanied by music from the visiting National Catholic Youth Choir, processed the final page down the aisle of the church and placed it on the altar.

“There was just a real reverence,” he says. “You could see that his work was coming to an end after all these years.”

Jackson had prepared the page with gesso to receive the final marks, which were applied by Abbot John Klassen, OSB; and Fr. Robert Koopmann, OSB, then-president of the University; each of whom completed a Saint John’s Cross in the page’s bottom corner.

“We were taking this manuscript that was created elsewhere, and marking it with the sign of its new home and really completing it,” Ternes says. “There was a real spirit of energy and excitement that this had happened.”

Fr. Patella adds further context about how remarkable the achievement was. “We realized in the process that if we were to complete this Bible, it would be one of the very few complete biblical manuscripts in the world, because it is a huge project.” He explains that it was only late in the medieval period that scribes even attempted “the great pandects”— binding the Bible as a single volume instead of individual books, such as Psalter, Gospels, Letters, etc.

“Among those that tried, some never got past a quarter of the way,” he says. “Some got three quarters of the way; some finished everything but the last three books because earthquake, war, plague—any number of things would stop it in its tracks.

“So as we started coming towards the end,” Fr. Patella recalls, “our prayer was, ‘Please, let us just complete this.’ When it was finally finished, when we got the final mark on, it was like, ‘By God, we did this thing.’”

Thinking back on the ceremony at the Abbey Church, Fr. Patella says, “That was a thrilling moment. It really was—when we realized we’d completed it, that we were a part of all this.”

Sharing the Legacy

Members of the CIT were finally able to share their excitement in their achievement at the event reception, where additional pages were displayed and attendees were able to ask them questions.

“Up to that point in time the artists were, deservedly, the people who got all the attention, but the CIT represented the Saint John’s portion, so we wanted to highlight them,” said Ternes. “They stood by the pages and for the first time people had a chance to see the results of those conversations they’d been having for 12 years,” he said.

The fellowship continued at a dinner in the Guild Hall that evening, which included “all the people who had anything to do with the Bible,” says Fr. Patella. “Everybody was there, and we all realized this could not have been done outside of this community effort. And that was thrilling. We were all involved; we all did it. It was like the church in miniature,” he says.

Of course, the Bible’s completion on that day in June was only the beginning of its story. “At that dinner, Donald Jackson said, ‘We’ve created this and we give it to you,’” says Ternes, “‘but the legacy won’t be the fact that it was created. The legacy will be what you do with it.’”

Come back to this blog next month for more reflections on the legacy of The Saint John’s Bible, its permanent home at Saint John’s, and its travels and impact around the world.