Beauty for Ashes: How Artisans Made the Ink Used in The Saint John’s Bible 200 Years Ago

The ink used in the creation of The Saint John’s Bible was made 200 years ago in China. Here’s how it was made and why artistic director Donald Jackson chose it to lay the foundation for this magnum opus.

The methods of crafting the ink used in The Saint John’s Bible, the first manuscript commissioned by a Benedictine monastery in more than 500 years, prove the phrase true: Everything old is, in fact, new again.

The question of what material would be best to immortalize the hand-written Word of God for the 21st century is not one that the project’s artists underestimated. After all, one of the foremost goals of the project is for the manuscript and all its facsimiles to be crafted with such care that the works will last upwards of a millennium. More often than not, the processes that ensured the highest quality and longevity were far from modern.

“Any medieval scribe coming to life today would recognize every single tool used in the making of The Saint John’s Bible,” said Tim Ternes, Director of The Saint John’s Bible at HMML.

In a series posted to the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML) YouTube channel, Ternes dives into the historical origins of the tools, methods, and materials used in making The Saint John’s Bible. One segment of the series, titled Ancient Methods, Modern Results, focuses on the inks used to create the work of sacred art.

So, how did Donald Jackson, former Senior Scribe and Illuminator at the Crown Office in the House of Lords and Artistic Director of The Saint John’s Bible, choose the inks that would do due justice to this work of biblical proportions? And how was that ink made and acquired?

Many Recipes Survive Today: Gall Ink

First, Jackson took stock of all of his options, which fit into two main categories: carbon-based ink and metal gall ink. Galls are swells that form on oak trees when a wasp lays its eggs on a growing bud of a tree. As the larva develops on the bud, a soft sphere grows around it. When the wasp is mature, it bores its way out of the gall, leaving behind a dried gall nut.

Most ancient recipes call for first crushing the gall nuts and soaking them in rainwater or vinegar in the sun or near a fire for several days. (According to one old recipe, you can speed up the process by boiling the crushed gall nuts in water as long as it takes to say the Our Father prayer three times.)

Other recipes call for soaking the gall nuts in the finest quality beverage one can afford. Once the water or other liquid is sufficiently dark brown, it’s time to strain the nuts out of the liquid and mix iron sulfate into the solution. Many ancient artisans acquired iron sulfate by soaking rusty nails in vinegar. When mixed with the gall liquid, the solution turns black almost instantaneously.

At this point, the mixture is still very thin. To add viscosity to the solution, it was common practice (and still is) to add gum arabic to the mixture. Gum arabic comes from boiling the dried sap of acacia trees.

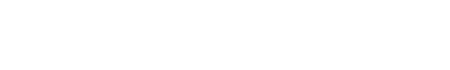

Gall ink has a beautiful, rich color and wonderful texture for calligraphy. However, because it is so rich in acids, over time, the ink starts to eat away at the page that it rests upon. For The Saint John’s Bible, which is intended to be seen and touched by multiple generations of humans, this characteristic took this kind of ink out of the running immediately.

So it was decided: carbon-based ink it was.

Chasing Ink Across the Globe

The ink used in the creation of The Saint John’s Bible is indeed carbon-based. It also dates back to the 1800s and originated in China. It was, as the name suggests, made of carbon. The most common source of carbon during this time period, long before, and even today is soot, otherwise known as lampblack.

The traditional method for collecting soot involves burning charred pine tree roots, which are very oily and resinous and produce dark and rich soot. In contemporary times, this oily substance is usually tung oil from the tung tree.

To begin the process, artisans place the tung oil in a bowl with a wick and let it burn. Then, they cover the bowl with porcelain cups that collect soot as the smoke rises and hits the cooler porcelain piece. Then, they brush it off and collect the pile. Soot produced in this way is a precious commodity; one entire day of burning 120 lamps, for example, only produces four ounces of soot.

Once the soot is collected, the next step is to thicken it to a paste. To do this, the most common thickeners are gum arabic or bone glue, which comes from the hides and bones of horses and cows. Some old recipes even use egg whites and honey as binding agents. The gum or glue is mixed with the soot until a dough-like texture is formed. Next, you pound the mixture and knead it, just like you would with dough for pie, bread, or other pastries.

Now that the mixture is complete and has the right consistency, artisans can mold and trim the mixture to whatever shape they desire. (The carbon-based inks used in The Saint John’s Bible are about four inches long and take on a rectangle shape.) Once the ink is molded and trimmed, it must be air-dried for three months to two years. The two most common ways to go about this are by hanging the ink in linen bags from the ceiling or simply laying it on shelves. The final mixture is 10 parts soot and six parts glue. The final, shaped mixture is glazed with glue on the outside so as not to stain the hands of the artist when it is ready for use.

Once it’s ready to use…

Once the ink has been left to dry for an appropriate amount of time, it is ready to use right then and there or even several centuries from then. When preparing the ink for use, an artist takes the ink stick in their hands, adds water to a grinding stone, and grinds the tip of the ink into the stone, breaking down the soot and glue and rehydrating the glue. Knowing when the ink and water mixture reaches the perfect viscosity takes a practiced eye, but if it looks slimy, that’s a good indicator that the mixture is ready for use.

“As a skilled calligrapher, you know when it’s going to be the perfect thickness for your pen,” said Ternes in the video.

That is precisely how the ink sticks used in The Saint John’s Bible were crafted in China in the 1800s. Donald Jackson himself was the one who found and purchased the ink sticks from a company in London called Roberson & Co, which has since closed. Jackson used to shop at the store in the 1960s and 70s. That’s where he learned that these sticks were brought over to London in the 1800s on sailing ships shipping tea from China. Over time, he acquired 144 sticks for two shillings per piece (about 12 cents each).

By the time Jackson started planning The Saint John’s Bible, he had given so many of these sticks away as gifts that he didn’t have enough to carry him through the creation of an entire hand scribed Bible. He searched for more but was met with a shockingly high paywall. Now in the 1990s, these ink sticks were regarded as collector’s items.

So, he resigned himself to defeat and began ideating a new ink that could carry him and his colleagues through the project. That is, until one day when calligrapher Sally Mae Joseph was giving a lecture to fellow calligraphers. Joseph mentioned her and Jackson’s desire to use these precious ink sticks in the creation of this new monumental endeavor. To her surprise, someone in the back raised their hand and spoke. Apparently, Donald Jackson gave this person several of these ink sticks years ago as a gift. The ink sticks were still in this person’s possession, and they generously offered to return them to Jackson’s collection.

After that first instance, word that Jackson was trying to re-acquire as many of these ink sticks as possible spread quickly. More and more folks reached out to Jackson and Joseph, offering to return the beautiful sticks of black carbon-based ink. Soon enough, Jackson once again had enough to scribe the entirety of The Saint John’s Bible with this precious ink.

What about red (vermillion) ink?

Those who noticed that black isn’t the only color of ink used in The Saint John’s Bible might be curious as to how the red ink is different from the black. The red sticks of ink (found in the kites or footnotes of The Saint John’s Bible) were also made in the late 1800s by a company that closed in 1867, meaning there is a

These red sticks are called vermillion sticks and are made of ceric sulfate mixed with egg white, gum arabic, and sometimes even honey.

The lore of Jackson’s acquisition of the red ink sticks is similar to that of the black ink sticks but is arguably … sneakier. Donald’s contact, a shopkeeper in London, did not want customers buying more than one or two sticks at a time. So, intermittently, Jackson came by the shop and bought just one or two sticks at a time. The trick was that he persuaded friends of his to do the same. When the shop owner decided to cease operations, Jackson tried to buy all of the ink he had. The shopkeeper refused, but Jackson was determined to get his hands on as many of these beautiful vermillion sticks as possible.

So, he researched the shop owner and followed the grapevine back to the shopkeeper’s supplier. Jackson then discovered that the supplier had two thousand vermillion sticks in his possession. Jackson bought every single one of them for pennies each. Each stick was still wrapped in the original papers from the 1800s.

Indubitably, a significant part of the magic that is The Saint John’s Bible stems from the materials that it consists of. Still, in the words of Tim Ternes, “No matter how exquisite the tools, it still takes a talented scribe to bring those tools to life on the page.” For that, we can thank Jackson and his team for their calligraphic artistry and vision.

The Saint John’s Bible: Bringing the Word to Life on Vellum

To read more stories similar to this one, visit The Saint John’s Bible Heritage Program blog or subscribe to our monthly e-newsletter.