International Space Station, 248 miles above Earth’s surface – Far away from the familiar green, gold and brown hues of Mother Earth’s palm, astronaut Mark Vande Hei lays in a near-fetal position with his knees pressed to his chest. He is a co-pilot on a small, Russian spacecraft whose thrusters are in the active phase. During this time, the astronauts inside the vessel feel about 3G’s (three times the normal gravitational force that one experiences on Earth’s surface) pressed directly into their chests.

For the first time in his career, he is preparing to orbit the Earth on his way to the International Space Station (ISS). Launched in November 1998, the ISS is an international space laboratory on which astronauts and cosmonauts conduct space research. According to The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the spacecraft travels at 17,500 miles per hour and orbits Earth every 90 minutes.

Finally, the third and final thruster stops firing. The gravitational force gluing Vande Hei to his seat diminishes to tolerable levels, followed by a new unsettling sensation of falling forward, suspending Vande Hei’s stomach despite being firmly strapped to the spacecraft. Unsettling as it is, this is exactly what is supposed to happen. The ever-present falling sensation signals that the spacecraft is finally in orbit.

“It’s very unsettling, lots of new sensations, that sense of falling. In fact, once you’re in orbit, you literally are just falling towards the center of the earth all the time, but we’re moving so quickly horizontally, that we keep missing the earth. But I remember feeling like it was just amazing,” said Vande Hei of the experience. “That’s all being in space is, at least being in orbit around the earth is. Falling.” Once in orbit, the astronauts have approximately six hours of falling left before reaching the ISS.

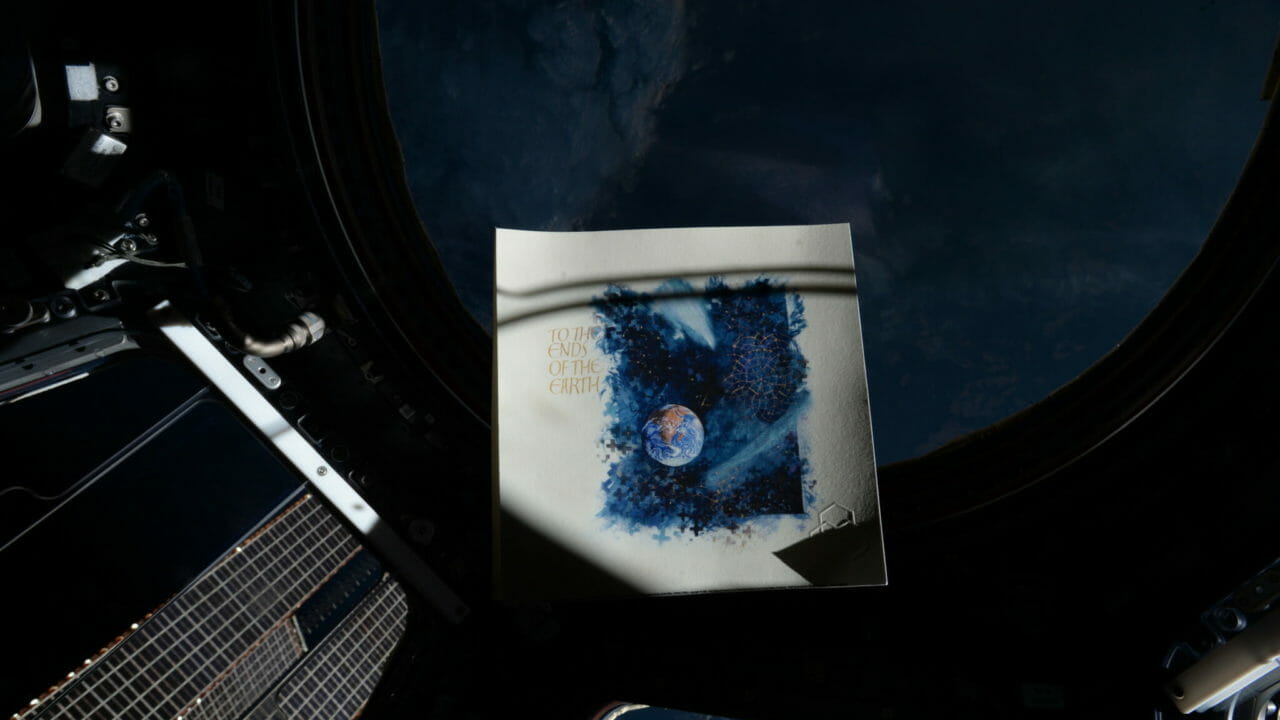

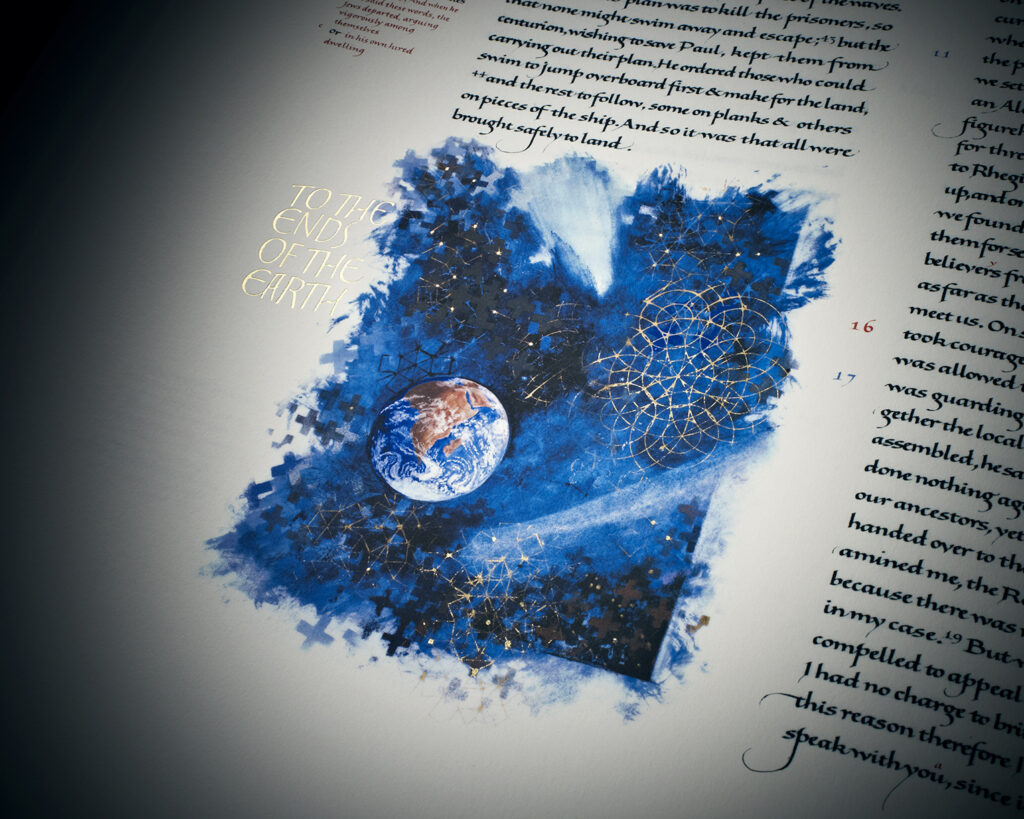

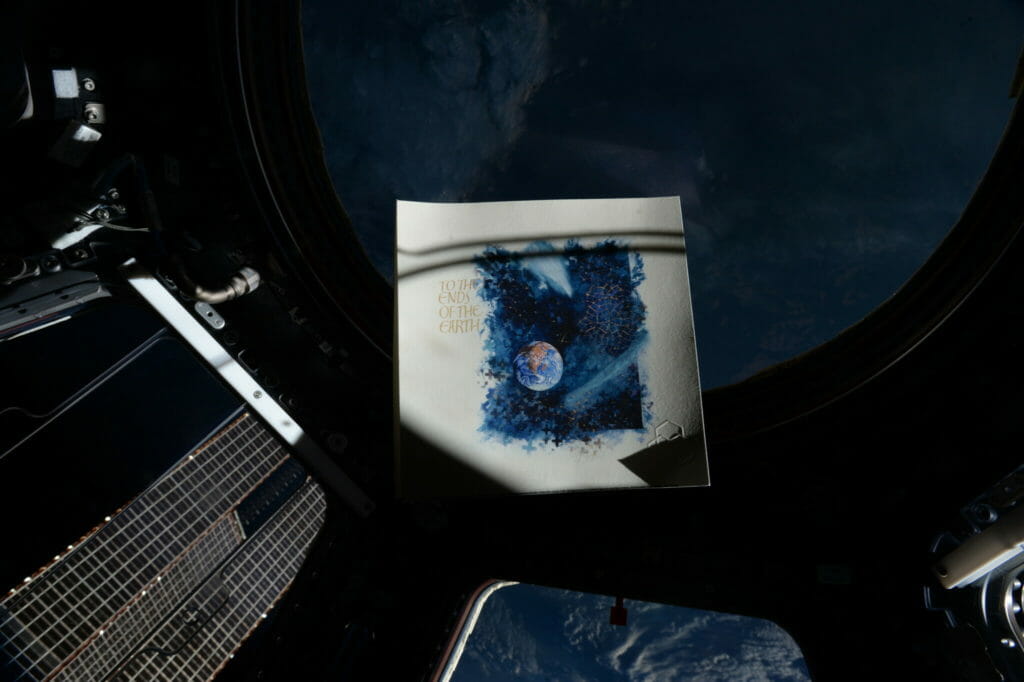

Squished inside what is easily the tightest quarters that exist outside of the earth’s atmosphere, there is only room for essentials on the vessel. Vande Hei’s attention is laser-focused on flying the spacecraft, but if any brave observer could perform a quick scan of the vessel’s cabin with x-ray vision, they would find a treasure: tucked securely among those essentials is an illumination from The Saint John’s Bible, titled“To the Ends of the Earth.”

This illumination is a special one. Plucked straight from the final page of the Gospels and Acts volume of the work, the illumination was crafted using a view of planet earth inspired by the Apollo 8 mission. The brushstrokes and colors of this particular piece of art, were painstakingly and thoughtfully executed by Donald Jackson, Artistic Director of the project and world-renowned calligrapher, with contributions from Sally Mae Joseph and Andrew Jamieson. The artists collaborated to conclude this volume with a striking invitation to examine humanity’s place among the cosmos – a perfect Earthly token to serve as a companion on Vande Hei’s trip to the Heavens.

168 Days of Falling, Falling, Falling

The space station has been continuously occupied since November 2, 2000, but Vande Hei’s first time on the station occurred in 2017. On his first space flight, Vande Hei lived on the International Space Station for 168 days, alongside two Russians, three Americans, an Italian astronaut, and, in the second half of his journey, one Japanese astronaut. Vande Hei returned home from his second space flight in 2022, extending the record for a continuous US spaceflight to 355 days.

“I remember some great moments when someone would say, ‘Hey, we’re flying over the Northern Lights,’ and, we’d cram five people into the cupola (a small, dome-shaped window through which those on the ISS can gaze outside) whispering to each other, because somehow it just seems more appropriate to whisper,” said Vande Hei. “It’s similar to being in a cathedral, these amazing moments in the dark in the cupola with all the lights turned off and seeing this constantly changing Aurora Borealis with fellow astronauts from all across the world.”

Busy as he was, Vande Hei, who graduated from Saint John’s University in 1989, had no shortage of sacred moments such as this during his time on the ISS. Conceptualizing outer space, let alone living in it, can seem as foreign or daunting as existing in an entirely different reality. However, the laws of physics don’t actually change in “outer space.”

“We have this sense that space is someplace else, when really we’re in it all the time,” said Vande Hei. “When you go outside and look up at the stars, you’re just standing on a surface looking at the rest of everything else. It’s like we’re a microorganism in a puddle in a parking lot, and that’s what the atmosphere looks like from outside. It feels, to me, much more like we are not separate from space.”

Mass is subject to the same conditions of the universe within and outside of Earth’s atmosphere. However, one’s perspective and physical relationship to those conditions change in a very significant way on either side of the veil.

For example, the space station completes 16 orbits of Earth in 24 hours. This means that astronauts and tourists on the space station witness 16 sunrises and 16 sunsets on any given “day.” Because the astronauts are outside of Earth’s atmosphere, sunlight isn’t scattered like it is on Earth. In fact, sunlight appears similar to a spotlight, rather than a soft sprinkling of warmth.

“It’s a very surreal feeling. It was just a little unsettling, even though it was beautiful,” said Vande Hei. “Looking back on the atmosphere from outside of it, it dawned on me that the atmosphere is a very special place that is very worthy of protection. I contemplated how the whole solar system is illuminated by sunlight, but there are very few places on planets that collect enough atmosphere to the point that sunlight is scattered, and the one we are in happens to be perfectly suited for life to form.”

Larger than a Molecule, Smaller than a Planet, Much Smaller than the Universe

When the time came for Vande Hei to take a photo of the “To the Ends of the Earth” illumination from the cupola, all these ideas and more were swirling through his mind.

“The illumination is certainly iconic, but what was special about it to me was this awe-inspiring idea of where humanity, in general, and even an individual human fits in a very, very small piece of the universe,” said Vande Hei. “That’s a very real experience when you’re in orbit, looking at the earth, and being able to see places that you recognize but at a scale that you’ve never experienced before. It makes you feel incredibly small, and it’s much like the mysteries of faith. It’s hard to get your head wrapped around it.”

Hard is an understatement. Though he was equipped with the illumination as a spiritual token from home, decades of research in astrophysics, a real-life visual of the Earth from 250 miles away, and fellow astronauts who were moving through similar emotions — by the end of his first time on the ISS, Vande Hei still felt lost. Counting down the days until re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, he was all the more disheartened by his own confusion.

“You tend to think about your own mortality before you’re going to go through the heat of reentry in the atmosphere. That perception of being so small and insignificant really hit home for me before I went home,” said Vande Hei. “I was really having a hard time. I felt like I needed to come home with a changed perspective, and I wasn’t sure I had it.”

Thankfully, in the days before his scheduled return home, Vande Hei found a moment of solitude to watch a movie. The chosen movie was 25 in 24, a film about the American rock band Switchfoot’s attempt to perform 25 concerts in 24 hours.

Alone in his crew quarters, Vande Hei watched as a scene played of the band tucked into their van at 3 a.m., finding a moment of peace together before they would go on stage yet again. “One band member said something that really helped me,” said Vande Hei. “He said, ‘I think we’re all God’s song.’ Somehow that made me feel like I didn’t have to figure everything out. I didn’t have to make sense of it all. I just had to play my notes in the song.”

The Saint John’s Bible Heritage Program: Pushing Curiosity to the Ends of the Earth

For more stories similar to this one, visit the Heritage Program blog, or subscribe to the program’s monthly e-newsletter, Sharing the Word.