From Feathers to Script: How to Craft the Perfect Quill with Tim Ternes, Director of The Saint John’s Bible at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library

Learn about the ancient methods of cutting a quill, a practice passed down over eight centuries and used by The Saint John’s Bible calligraphers, with Tim Ternes, Director of The Saint John’s Bible at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library.

Ancient texts endure the passage of time due to deliberate craftsmanship and the meticulous tools employed during their creation, underscoring the rationale behind their resilience. Even so, while The Saint John’s Bible was completed in contemporary times and stands as a modern masterpiece, its production mirrors methods from centuries past in a remarkably similar manner.

Under the art direction of Donald Jackson, former Senior Scribe and Illuminator at the Crown Office in the House of Lords, he and his team of scribes deployed traditional methods not only to recreate the past, but because there is no better way to go about it.

For more than fifteen hundred years, Benedictine monasteries have acted as producers and protectors of ancient texts and books, and in keeping with that heritage, created The Saint John’s Bible through a process that reflected that of its medieval predecessors. Hand-written on vellum, using quills, natural handmade inks, hand ground pigments and gold leaf, The Saint John’s Bible is the first of its kind in 500 years to illuminate the Word while incorporating modern themes, images, and technology of the 21st century.

In a video posted by the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library Youtube channel, Tim Ternes, Director of The Saint John’s Bible at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library at Saint John’s University provides an inside look at the historical roots of the tools, methods, and materials used in the making of The Saint John’s Bible through his web series “Ancient Methods, Modern Results”.

This specific talk explores the most fundamental tool with which every scribe needs to write a quill.

Chronicling a Timeless Tool

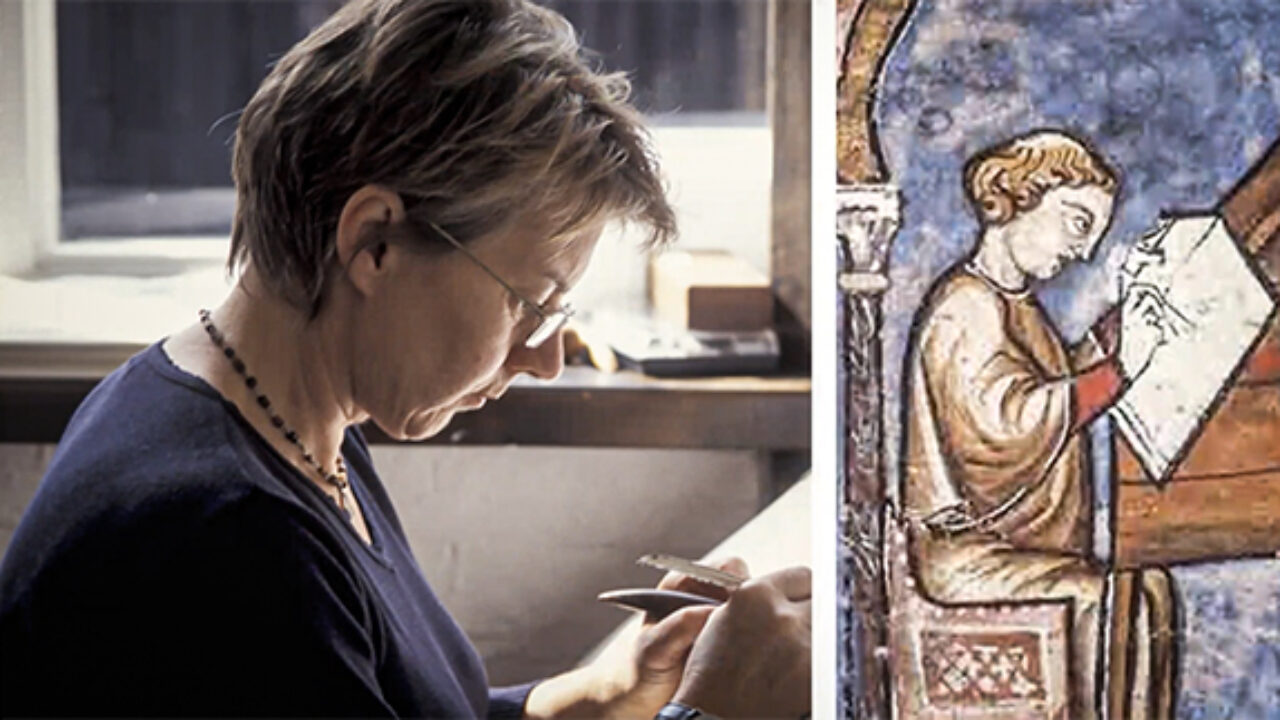

Traditionally, medieval scribes worked in scriptoriums dedicated writing rooms in European monasteries for the copying and illuminating of manuscripts.

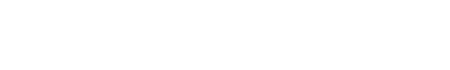

800 years later, nearly identical methods were practiced by a team of expert scribes who spent their days within a scriptorium in Wales. From 1998 to 2011, this team worked as a collaborative unit, spending hours perched over precious pages of vellum as they scribed each letter of The Saint John’s Bible by hand.

As one observes the images above, consider the similarities with which each scribe demonstrates proper technique: from their pen grip to the angle of their body in relation to the page. Even eight centuries past, you’ll notice that not much has changed.

Contrary to the countless medieval recipes passed down from the Middle Ages for making inks, there are no written instructions for how to properly cut a quill. The reason for this may be how common a practice it was to the educated population over time – just as one knows how to sharpen a wood pencil, scribes know how to cut their own quill.

Crafting an Authentic Quill

While The Saint John’s Bible scribes vary in their individual approaches, the art of cutting an authentic quill remains the same. The process is so similar to that of medieval scribes that if we were to bring one back to life, they would readily recognize almost every step of today’s practice.

From medieval times to the present day, the process always begins with a feather. The Saint John’s Bible scribes used turkey, swan, and goose feathers, though it doesn’t matter what kind of feather you use it’s all about the skilled cutting of that quill.

But you do need a feather to start.

The best and strongest quills come from the front three flight feathers of the bird. You also want feathers from a mature and undomesticated bird to ensure the highest quality and strength. Ideally, right-handed calligraphers will take their quill from the left wing, and left-handed calligraphers would take from the right wing to make for a natural fit in their hand.

However, a feather alone is still not strong enough to be a quill just yet. A feather shaft is the same fragile material as your fingernails, and there are a couple of necessary steps to follow in order to prepare the feather to be cut into a quill.

Step #1: Trim off the bottom of the feather and soak it in water for 24 hours

A scribe will also at some point shave off the outer membrane of the shaft and clean out the inside to make the feather hollow. Even then, the feather is still not ready to be cut. In this condition, the feather is too soft and would break down immediately if punctured by a knife.

Step #2: Harden the quill with heat

The best way to harden a quill is to apply heat. The Saint John’s Bible team typically poured hot sand (heated to 350 degrees Fahrenheit) into the hollow shaft of the feather, allowing it to slowly harden and clarify. It’s important not to overdo this step or the feather will become too brittle to use.

Step #3: Remove the barbs from the feather shaft

If you look at any medieval painting, you will see that none of the quills have big, bushy tails like they do in television shows. The barbs are only there to capture and resist the wind, so scribes cut them away, making their quills slim, beautiful, and elegant. Scribes will also cut the tip of the feather off and trim it to their desired length.

Step #4: Shoulder cut

Here, a scribe will use their pen knife and make some cuts into the barrel of the feather, shaping the neck down to the shoulder.

Step #5: Cradle Cut

The cradle cut transforms the feather into the standard look of a modern fountain pen. Scribes all naturally cut towards themselves, giving them more control over their knife to make precise cuts along the barrel and shaft.

Step #6: Create a slit

This slit at the end of the shaft creates a capillary for ink to flow out of the pen.

Step #7: Nibbing

Finally, a scribe will use their pen knife and cut straight down on the tip, shaping it into a fine, chiseled edge.

Step #8: Sit back and admire your work!

The making of a quill is second nature to many calligraphers. Across hundreds of years, this process has remained a crucial step in manuscript copying and illuminating. It’s only when you strip the process down to its roots that you realize how unique The Saint John’s Bible truly is. That when you look at the tool resting in an artist’s hand, no matter how they choose to cut their quill, you can see the magic that can be made from a turkey feather and pages of vellum.

The Saint John’s Bible Heritage Program: Applying Ancient Methods for Modern Results

To purchase a quill of your own, check out www.dennisruud.com/quill-pens.

For more information and inquiries about The Saint John’s Bible Heritage Edition and original manuscript, contact Tim Ternes at tternes@csbjsju.edu

To read more stories similar to this one, subscribe to the Heritage Program’s monthly e-newsletter, Sharing the Word, or visit the blog.