Connecting the Benedictine Preservation of Ancient Texts and The Saint John’s Bible

The roots of The Saint John’s Bible began far before its commissioning in 1998 and even before the childhood dream of artistic director Donald Jackson to handwrite the Bible. The ancient tradition of manuscript writing can, in fact, be traced all the way back to the Rule of Benedict itself conceived and written by Benedict of Nursia, known as the “Father of Western Monasticism” at Sacro Speco cerca 529 AD.

Permanently embedded along the rock face of Monte Taleo near Subiaco, Italy, the Sanctuary of Sacro Speco has remained a holy place of worship since the sixth century. Between the architecture and living rock, this Sanctuary, otherwise known as the Cave of Saint Benedict, marks the beginning of a new tradition and order, one that has since been passed down for more than 1500 years.

Here, Saint Benedict of Nursia (480-547 CE) wrote the Rule of Benedict the core of Benedictine religious practices that are still used to this day in Benedictine communities worldwide.

This is the birthplace of the Rule of Benedict.

The Rule is rooted in Saint Benedict’s own long experience as a monk and Abbot. It references the older monastic traditions, prescribing times for common prayer, meditative reading, and manual work. A manuscript in of itself, the Rule of Benedict sparked a long tradition of book production, textual preservation, reading, and study. By directing monastics toward meditative reading of sacred texts, the Rule has inspired centuries of monastics to care for the written words to which they devote their lives.

Though not encapsulated by ancient rock and surrounded by the natural flora and fauna of Subiaco, Italy, The Saint John’s Bible offers a beautiful manifestation of the modern Living Word the most recent extension of the work conceived in the sacred cave.

The Saint John’s Bible Heritage Program invites you now to take a glimpse at the legacy of Saint Benedict and the Rule that guides the practices of thousands of monks, nuns and religious individuals.

The Art of Benedictine Manuscript Preservation

Throughout history, the Benedictine Order has upheld a belief in the power of sacred texts. In a way, sacred manuscripts are humankind’s most successful attempt at time travel. It’s because of those who preserved these works before us that we are able to continue learning, worshiping, and making sense of them.

The early labor of copying and writing texts resulted in the humanistic principle of learning from other people and cultures. To understand one another, we must listen to each other in our native voices and words to capture the essence of differing beliefs. The Benedictine Abbot Peter the Venerable knew this, and in 1142, he traveled to Spain where he summoned Christian scholars of Arabic to translate Islamic texts including the Qur’an itself.

Among their original works of theology, literature, history, and science, Benedictine monks are well known for their copying of manuscripts in the Dark Ages (476 AD – 1000 AD). Manuscripts handwritten books are by their very nature entirely unique and are kept alive to this day through tender and precise care.

It’s important to note that history does not always rely on the truth of the past, but also the promises of an ever-changing future. Traditionally, Benedictine monks are adopters of new technologies. In the 1560s, the first printing press in Italy was established at the Sanctuary of the Sacro Speco. As the Benedictine Order expanded into the New World, Bavarian Benedictines established another printing press at Saint Vincent Archabbey, located in Latrobe, Pennsylvania—the oldest Benedictine Monastery in the United States, and the largest in the Western Hemisphere.

In 1856, four monks were dispatched from Saint Vincent Archabbey and moved to central Minnesota, where they founded the Saint John’s monastic community. A year later, they would launch Saint John’s University, a private, four-year liberal arts university. In 1926, the Liturgical Press was founded and Saint John’s Abbey would become internationally known as a Catholic and ecumenical publisher in prayer and spirituality, Scripture, liturgy, theology, and monastic life.

The Modern Living Word of God

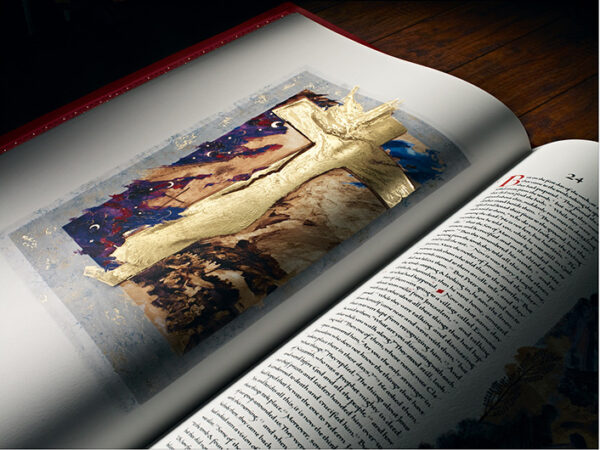

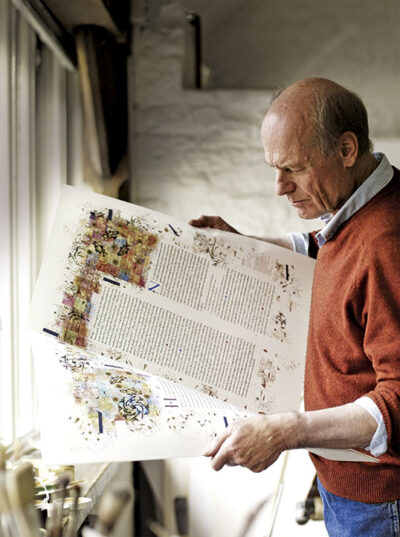

Perhaps the most recent reflection of the prolific traditions in manuscript creation and preservation is the great achievement of The Saint John’s Bible. In 1998, the monks of Saint John’s Abbey and University approved and commissioned Donald Jackson, former Senior Scribe and Illuminator at the Crown Office in the House of Lords, to direct a team of renowned artists, calligraphers, and printers to complete the canonical project one of the most exceptional artistic and technological endeavors of the new millennium.

After eleven years of hard work and dedication, the final words of The Saint John’s Bible were penned on May 9th, 2011. The manuscript is the first hand-written, hand-illuminated bible in more than 500 years, written on calf-skin vellum using only traditional tools and ink to ensure the quality and longevity of its beauty and form.

The Hill Museum & Manuscript Library is home to the original manuscript of The Saint John’s Bible. The individuals who work there uphold the traditions practiced by the Benedictine monks before them, ensuring that the sacred practices first conceived at the Sanctuary of Sacro Speco are honored and passed down to future generations to come.

The Saint John’s Bible Heritage Program: Preserving the History of Benedictine Order

To read more stories similar to this one, visit the blog or subscribe to the monthly e-newsletter, Sharing the Word.

To follow along with the Heritage Program in real time, follow @SaintJohnsBible on Instagram, Meta, and X.