Joslyn Art Museum Brings Original Folios of The Saint John’s Bible Back to Its Community

Handwritten pages make their way back to Omaha for the first time since 2006

Hosting original, handcrafted folios from The Saint John’s Bible is a luxury few places have enjoyed. The number of institutions that have done so twice is even smaller.

In 2006 – before The Saint John’s Bible was finished – Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha hosted Illuminating the Word, an exhibition of untrimmed folios from the three volumes of The Saint John’s Bible that had been written and illuminated as of that time. “The response to that exhibition was overwhelming,” says Taylor J. Acosta, Ph.D., Associate Curator of European Art at Joslyn. “It was one of the best attended exhibitions in the institution’s history.”

Now, Joslyn is pleased to bring The Saint John’s Bible to Omaha a second time through January 2020 with Word and Image, an exhibition organized by Joslyn Art Museum and Saint John’s University.

When the opportunity arose to host 76 completed folios in 2019, the stars were already aligned for the return of The Saint John’s Bible – a high concentration of alumni from the College of Saint Benedict & Saint John’s University; the presence of the Heritage Edition at three Omaha institutions; and the global appeal of the Bible among them.

Since the exhibition’s opening in October, Acosta says the Omaha community has welcomed the folios as warmly as they did more than a decade ago, due in part to what Joslyn has added for returning visitors. “We wanted to make Word and Image a new experience for visitors who may have seen Illuminating the Word in 2006. The exhibition is devoted to this one work of art, The Saint John’s Bible, and we wanted to present it in a variety of contexts.”

Those ‘contexts’ include sharing the methodology of creating The Saint John’s Bible as well as its place in the history of illuminated art and religious texts. Alongside the folios, Joslyn is exhibiting “the artists’ tools, materials, sketches, and drafts of the scripts, all to give our visitors insight into how manuscripts are made,” as well as “examples of medieval illuminated manuscripts, both from our own collection and from the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library [HMML], in order to situate The Saint John’s Bible within this longer history of illuminated manuscripts.

“Finally, we wanted to include examples of sacred texts from other religious traditions to underscore the importance of these types of books in shaping and representing the shared concerns of faith communities,” says Acosta. “So our exhibition includes a Torah scroll that is on loan from a local family and also examples of manuscript Korans” from HMML.

She says that Joslyn considered how the Museum might present and contextualize The Saint John’s Bible for this iteration. That’s ranged from lectures from faculty of Creighton University, which also hosts the Heritage Edition, to calligraphy classes for children and more.

“I’ve led a number of tours of the exhibition with people that range in age, cultural and religious background,” says Acosta. “People find ways to connect with The Saint John’s Bible, whether as a work of art or as a work of faith or as something in between the two.”

Working on her doctorate in art history at the University of Minnesota, Acosta was closer to The Saint John’s Bible project: She was in Minneapolis at the time of its original display at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Even given her prior knowledge of the project, visiting Saint John’s University in preparation for its return to Joslyn was formative for Acosta’s experience with it.

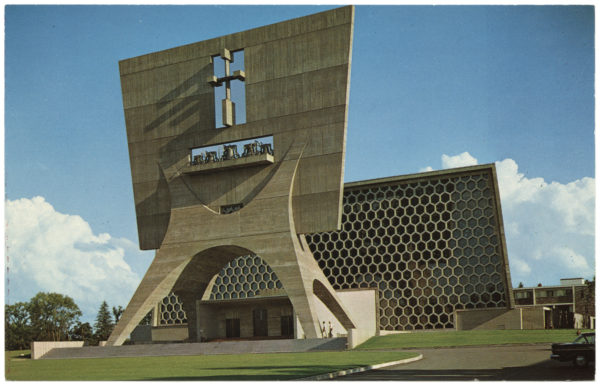

“The Benedictine monks of Saint John’s have such a respect for art that sort of reveres tradition, but it’s also very forward thinking,” she says, pointing out the iconic architecture of Marcel Breuer on campus. “So this idea of art that is rooted in tradition but embraces innovation was made more real to me seeing the campus and making those connections.”

Working closely with visitors – both to Word and Image and the rest of Joslyn’s artistic offerings – has leveraged Acosta’s perspective into how and why people experience art. “My area of focus is 19th-century French painting, but I like to consider myself an interested generalist, and I’m a student of history,” she says. “Of course for much of the European art that I’ve studied and that is represented in the museum’s collection, from the Italian Renaissance to Nineteenth-century France, the Bible was a primary source of inspiration.

“I think the fact that The Saint John’s Bible is a handmade object of the highest quality is very much foregrounded in any of the literature about it and certainly in our presentation of it,” she continues. “Even if one hasn’t studied the Bible in great detail, they can appreciate the enormous skill of this project. They may also have seen allusions to the Bible it in other forms of culture, art, literature, film. So I tried to bring all of that experience and interest to bear on really learning about and speaking about The Saint John’s Bible.”

Acosta’s perspective joins a number of curators and staff at Joslyn, all united by the Museum’s mission: “I think that’s part of a larger leading philosophy of the museum––to make art as accessible as possible to all different audiences.

“I recognized from the outset that these illuminations are very multivalent,” Acosta says. “They really reward sustained looking. And I hear that echoed back to me by the visitors; they feel compelled to come back again and again to look at these objects for longer periods of time.”