Imagination on Fire Uses The Saint John’s Bible as a Springboard for Incarcerated Artists

California program donates art supplies to artists behind bars to help them “give back

“Artists need to do art to be fully human,” says Rev. Nora Jacob. “They need to express themselves.”

But what about artists who legally can’t? Whose situation prevents them not just from sharing their art with the world, but from even acquiring the tools to create it in the first place?

Imagination on Fire, an art installation created by Chapman University and UrbanMission Community Partners (UMCP), sought to answer that question in California by combining the emotive ambition of incarcerated artists with art from The Saint John’s Bible.

Jacob is co-founder and Restorative Justice Director of UMCP and creator of InsideOut Art, a community initiative founded in 2015 that provides art materials to incarcerated artists in California so they can respond artistically – to their incarceration, rehabilitation, and their personal and spiritual journeys. Pieces are displayed in churches and galleries and sold, with a portion of the proceeds going toward more art supplies for the artists.

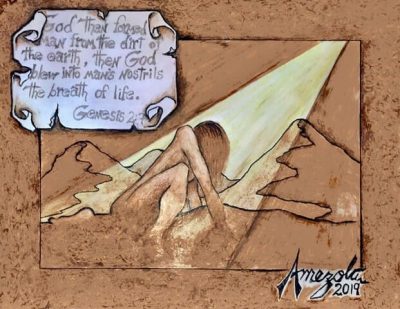

For Imagination on Fire, artists were given the opportunity to study art from The Saint John’s Bible (loaned from Chapman) and associated scripture. The concept was to allow these artists to relate their life experiences to the timeless art and message of the Bible, thereby creating new art to help others understand their own experiences.

The exhibition was the brainchild of Rev. Jacob and Nancy Brink, Director of Church Relations at Chapman. “It was a happy accident,” Brink says of the genesis of Imagination on Fire. “Nora was just walking through the Fish Interfaith Center at Chapman University and we started talking about The Saint John’s Bible and she had the brainstorm about connecting it to her work with people who are incarcerated.” As Chapman University finalizes their fundraising to acquire the Heritage Edition during their Year with The Saint John’s Bible, Imagination on Fire is just one of many ways the university plans to engage their community with The Saint John’s Bible, including regular visiting hours and events throughout the year. (Find out more at Chapman University’s website.)

Artists “Work from their Mind’s Eye” at the California Institution for Men

The majority of men behind bars at the California Institution for Men are going to be there for a long time. Opportunities like Proposition 57 – which authorized sentence credits for good behavior, education and rehabilitation – mean that “there are people going home every day,” says CIM Community Resources Manager Delinia Lewis, “but the large amount of our population are serving life sentences or LWOP” – life without the possibility of parole.

“Their families tend to move on with their lives,” says Lewis, “and say, ‘You made the choice to commit a crime that will take you from your family for life,’ so they move on with their life. [Prisoners] find themselves with no family, no resources, no funds to support their endeavors.” With little support outside the walls of prison, Lewis’s job is clear: “One key piece of our mission is to provide rehabilitative strategies to more successfully reintegrate our inmate population into the community.”

That’s what makes CIM’s partnership with Jacob’s organization so meaningful.

“Nora and I have a bit of history,” Lewis says. “She’s one of our premiere collaborators at CIM,” helping provide rehabilitative options like cognitive therapy and mindfulness in addition to artistic resources. “It gives a lot of inmates an opportunity to express themselves through art and develop their artistic skills and show it to the world.

“It’s a form of rehabilitation, as well – it’s paying restitution to the world by giving back something positive because they … have been taking from the world, taking from victims. This is an opportunity to give back – to give back a smile or joy,” Lewis says.

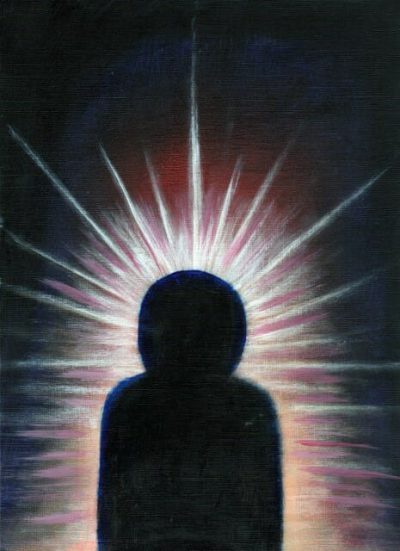

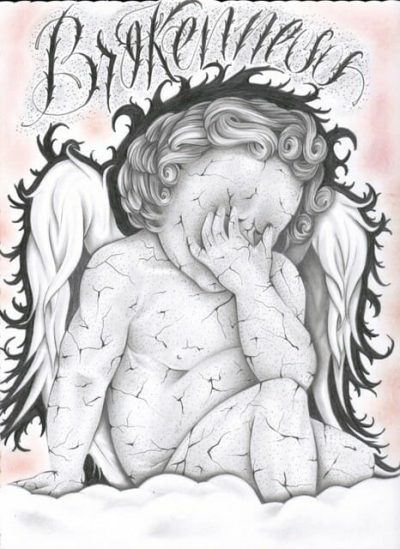

In many cases, Jacob says, incarcerated artists aren’t very verbally expressive. “Their way of expressing themselves is by painting or drawing or sketching,” she says, “working from their mind’s eye to present something.

“People have different learning modes,” Jacob says – “auditory, kinesthetic, visual, and so on. People effectively express themselves – their hearts, their pains, their joys – in different ways.” Some prisoners are word artists: poets, singers, and writers. “Those who work in paint and drawing and other visual artistic expressions are people who have found the most powerful way to share their truth, whatever that truth is.”

“We had an inmate; he didn’t know how to read or write,” Lewis relates. “He said his mother always said ‘he’s stupid like his father,’ so he never expected much of himself and of course he ended up with a life of crime that led him to CIM.”

LWOP.

“He did not know that he even knew how to draw, let alone be a prolific artist,” Lewis continues. “His art renderings go for, I believe, the largest sum of all the [CIM] inmates now. Now he’s allowed some of the inmate tutors to help him to read and write, and we found out he’s just dyslexic. He’s not dumb at all! Actually, he’s probably a genius, if you look at his art rendering. But now he has faith in himself … He’s brilliant and he’s a prolific artist.”

But just helping artists like that put their work out is only the beginning of the process for people like Lewis. “Now, his art is going for more than $500, $600. He could sell several art renderings a month and make a life for himself. But he did not know that before coming to this prison and being part of this program. So it’s life-affirming. Now we’ve given him a real skill that is legal where he can make an income for himself, he can work for himself and we’ve given him hope.

“That hope is going to ensure that he is not going to assault an officer or do something to endanger his life or someone else’s because he wants to continue the program and get credits and hopefully, with one of these propositions, or one of these new senate bills, have the potential to come out and be a productive part of society. I think it helps this come full circle. And we’ve given this person more confidence in himself, and now he believes in himself enough to learn to read and write.”

“They really want to continue participating” at High Desert State Prison

Jolene Speers, CRM at High Desert State Prison (a maximum-security prison in Susanville, CA), says there was no way to predict which artists were going to be interested in the InsideOut Art project when the opportunity arose. “It wasn’t any specific type of artist that participated,” she says. “We have drawing classes; however, very few submitted artwork for the show. It was really random who decided to participate, names I didn’t recognize because they don’t participate in a lot of groups, which was really nice.”

Despite that surprise participation – or maybe because of it – Speers says it was a definite success at HDSP. “Since it was our first art show, it’s hard to measure what the future of the program looks like,” she says. “If feedback is any indicator, from the viewing public or the creators themselves, the program should have a strong future.”

“The warden and I attended the art show,” Speers says. “We got a lot of positive feedback from the public bidding on the artwork, and those just wanting to see what it was all about. There were a lot of positive comments about the program and they were excited the inmates were allowed to participate.

“And as far as the inmate side of it goes, I’m constantly asked, ‘When are we going to have another art show? Do you need more artwork?’ So they’re ready to go. They really want to continue participating in the art shows.”

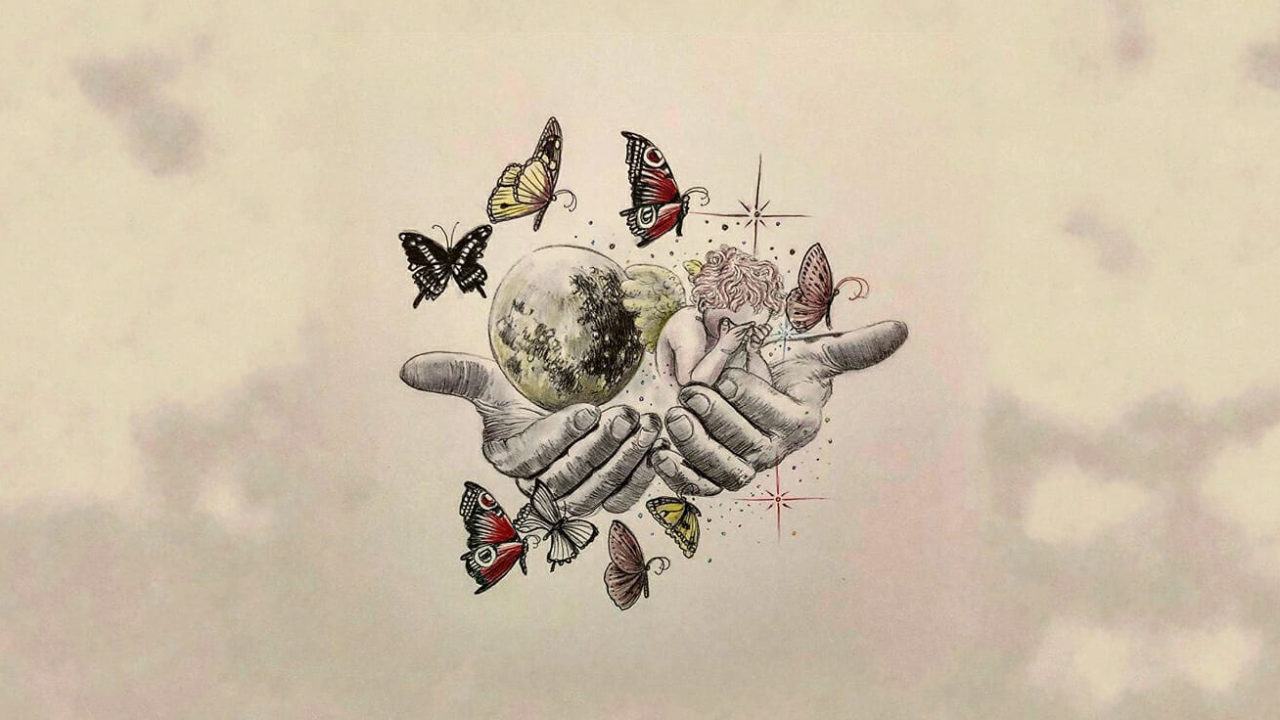

“Prison art” doesn’t quite describe what came out of HDSP’s artists. “We had hummingbirds, butterflies, portraits, superheroes,” Speers says. “There wasn’t a theme; they just submitted whatever they felt like drawing at that point in time.” The irony seems to surprise even Speers: “I don’t know exactly what I was expecting, but I wasn’t expecting such positive and uplifting subject matter.”

Invitations for Connection

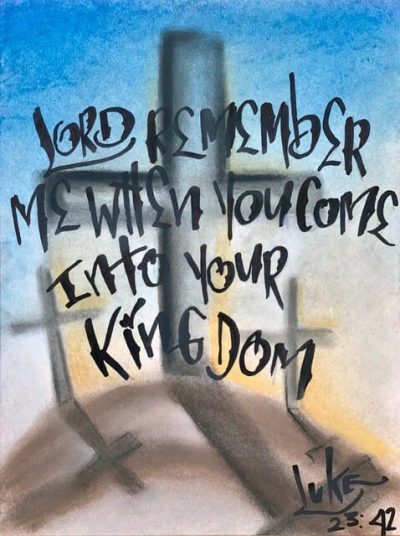

In Jacob’s view, Imagination on Fire worked in two directions: first, it allowed artists behind bars to express themselves in a way most simply don’t; but it also allowed them to see themselves in the artwork of others. She described one encounter with an incarcerated artist who seemed particularly taken with the custom script seen on the pages of The Saint John’s Bible. He was initially reserved – “uncertain about what [he was] being invited into” – but Jacob pressed him for his reaction.

“It was respectfulness, it wasn’t caution,” she says. “I pointed to the writing, the calligraphy” – from Genesis, she recalls – “and asked, ‘What do you see here?’ One of them said, ‘I know somebody who used to tag just like that.’”

That’s to say nothing of the effect the exhibitions have on visitors. “More than one in 10 Americans know someone currently in prison or in the system,” Jacob says, including people on parole or probation. “All of that comes up as people experience art that comes out of people who are incarcerated and who are expressing their truths. It’s a real invitation for connection, even though you’re not connecting with a person directly – you’re connecting with their artwork.”

Like many other exhibitions of art, Imagination on Fire and the greater InsideOut Art initiative highlight the power of art to inspire. What sets them apart isn’t the subjects or creators; it’s that they demand viewers to reconcile their concept of the origin and purpose for art itself. “Prison is such a controlled and isolated environment,” Jacob says. “[InsideOut] is a way to be recognized for your personhood.” Who’s capable of creating art; what it means to be capable; how we choose to use (or abandon) that capability for the betterment of ourselves and others.

“Our world is very verbally-centered,” Jacob says. “What if everyone in the world couldn’t speak for a week? I think we’d find hidden artists among ourselves.”