“Illuminating Justice” Interprets the Art of The Saint John’s Bible Through a Modern Lens of Social Justice

Women’s rights, environmentalism, religious conflict – Jonathan Homrighausen sheds light on them all using illuminations

For many, The Saint John’s Bible is a kaleidoscope through which to see our world – religion, society, war, politics and technology are just a few of the themes that scholars and students alike have been able to extrapolate from its pages and provenance.

Liturgical Press recently released “Illuminating Justice: The Ethical Imagination of The Saint John’s Bible” by Jonathan Homrighausen, which examines how the visual meditations of The Saint John’s Bible highlight the role of women in the Bible and in modern society. It is the first book to survey the Bible’s illuminations thematically as well as the first book about the project written by someone not involved in its production.

Homrighausen’s experience with The Saint John’s Bible dates back to his days as a student assistant in the Department of Archives and Special Collections at Santa Clara University, where he first encountered the Heritage Edition. His work toward a Master’s Degree in Biblical Studies naturally complemented his close proximity to The Saint John’s Bible.

Homrighausen said that his supervisors asked him to research The Saint John’s Bible to better facilitate student interaction, but that his time with the text became more than perfunctory. “I’m the kind of personality where I get into something and I really get into it,” he said, “so I just kept digging and digging.”

The seed for his book came as courses began to integrate the Heritage Edition into their curriculum. “There are these great books out there about The Saint John’s Bible,” he said – citing “The Art of The Saint John’s Bible” by Susan Sink and “Word and Image” by Michael Patella, who lent a foreword to Homrighausen’s book – “that go through illumination by illumination. I started to see connections between different illuminations – the way that the visual vocabulary of The Saint John’s Bible was repeated – and the social justice that the monks at Saint John’s Abbey wanted to put into this Bible.”

Among other themes covered in his book, Homrighausen noticed “the way that The Saint John’s Bible lifts up the role of women in scripture,” opening a path to dialogue in the context of modern feminist interpretation. That particular topic guided the focus of the chapter excerpted below, but other issues relevant to the modern world, including ecological responsibility and religious conflict, are also probed in “Illuminating Justice” – all inspired by the art of The Saint John’s Bible. As Homrighausen said, “Seeing a lot of these thematic connections – that was where my book was born.”

The following is an excerpt from “Tree of Knowledge, Tree of Life: Women and Wisdom Women,” the third chapter of Jonathan Homrighausen’s “Illuminating Justice: The Ethical Imagination of The Saint John’s Bible,” available now through Liturgical Press and Amazon.

Just as The Saint John’s Bible highlights the role of women at pivotal moments in ancient Israel, it also highlights pivotal women in the life of Jesus, from before his birth to after his resurrection. By focusing on the experiences of these women and their witness, The Saint John’s Bible engages in the remembering of women’s witness crucial for feminist biblical interpretation.

This remembering begins with the women important in Jesus’ life even before his birth. On the very first page of Gospels and Acts, Genealogy of Jesus, the frontispiece to Matthew, displays Jesus’ family tree as a menorah. While Matthew only mentions five women in the genealogy, Jackson incorporates all the women in his illumination, finding their names scattered throughout the Old Testament. The five women named in the genealogy do not paint a picture of Jesus’ perfect, priestly pedigree. Rahab the Canaanite and Ruth the Moabite are foreigners. Bathsheba and Tamar conceived their sons out of wedlock. Mary became pregnant while still betrothed, as, in Amy-Jill Levine’s “the divine family plan moves in ways that contravene traditional family values.”i Jackson’s choice to include all women—even Hagar—signals a strong feminist reading of Matthew’s genealogy, even as it lessens Matthew’s focus on outsiders and the marginalized.ii

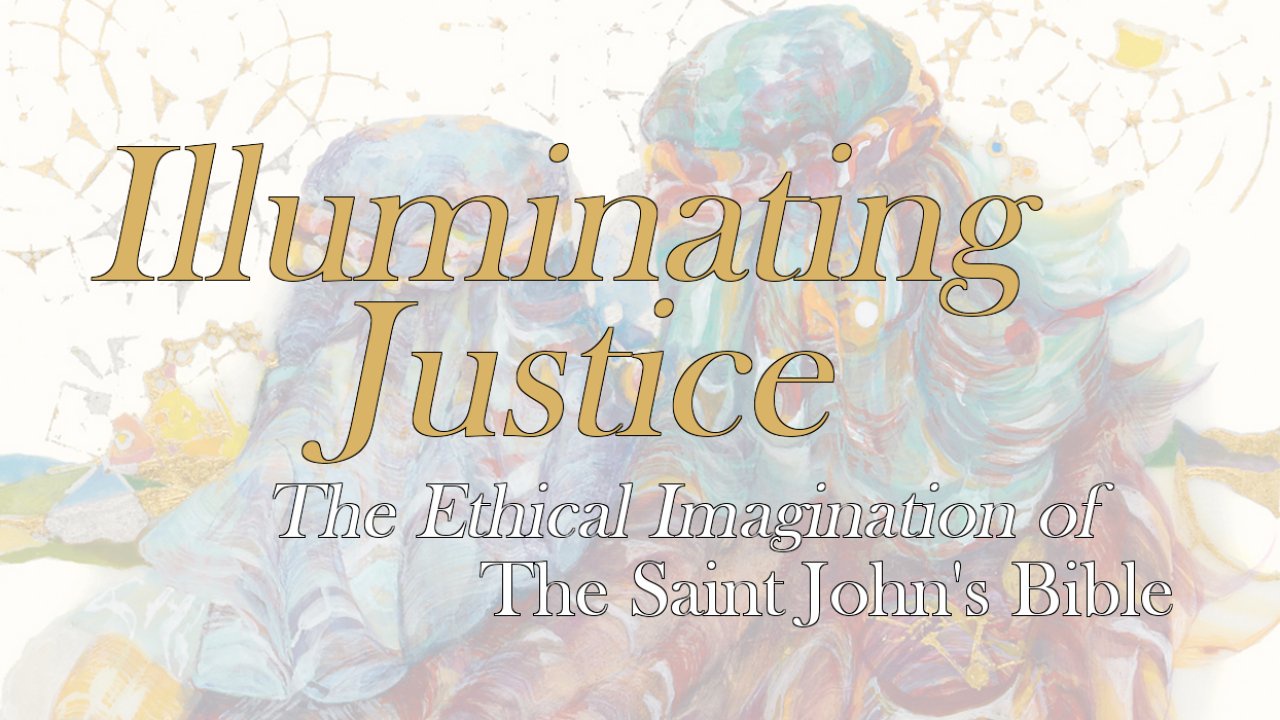

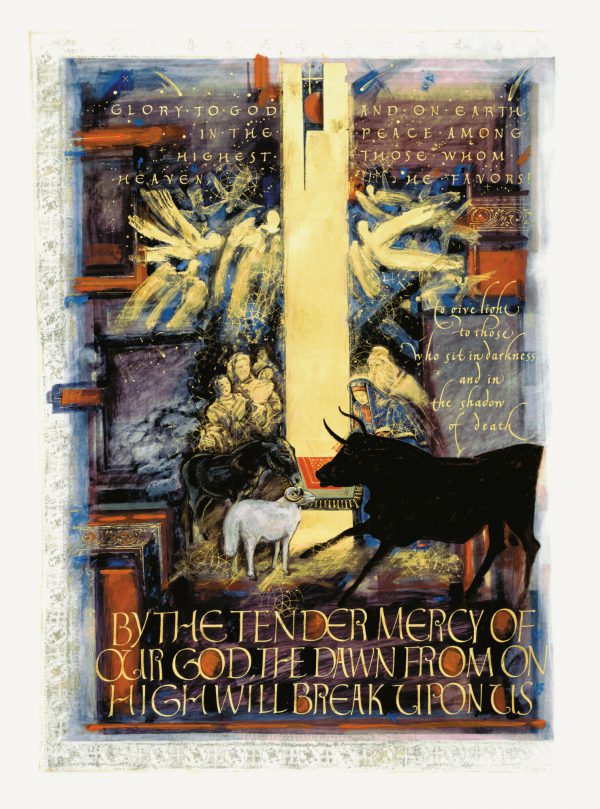

In one subtle symbolic connection, Jackson emphasizes the miracle of maternity in the birth of Jesus. In Birth of Christ, the frontispiece to Luke, Jackson supplies the only illumination of Jesus’ mother Mary in The Saint John’s Bible. Here, she leans joyfully over the manger, with its Jesus absent because we are to place him there in our own lives.iii On the next page, Mary’s Magnificat is augmented with a special text treatment in radiant gold.

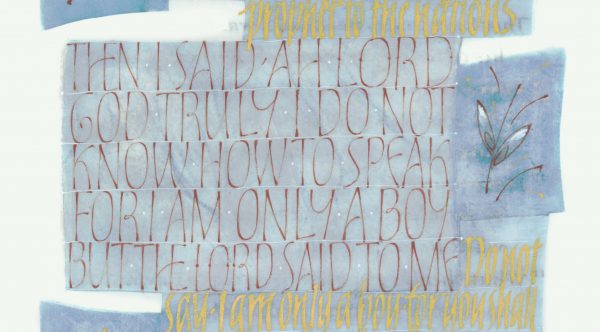

The Magnificat is not only central to Catholic devotion and liturgy, but also to feminist biblical interpreters such as Jane Schaberg who deem it “the great New Testament song of liberation … a revolutionary document of intense conflict and victory,”iv and from it argue that Mary is a prophet.v The Saint John’s Bible connects Mary with the Old Testament prophetic tradition by using the same script and chrysography—gold letters—to write God’s words calling Jeremiah to prophesy.

Just as Jeremiah is consecrated to be a prophet while in the womb, so Mary serves as a prophet while Jesus is in her womb, and likewise the fetal Jesus is called to be a prophet before his birth. Both the background of Magnificat and Mary’s cloak in Birth of Christ are in the royal blue traditionally associated with Mary—though supplemented in Birth of Christ by Mary’s bold red shirt under her cloak.vi

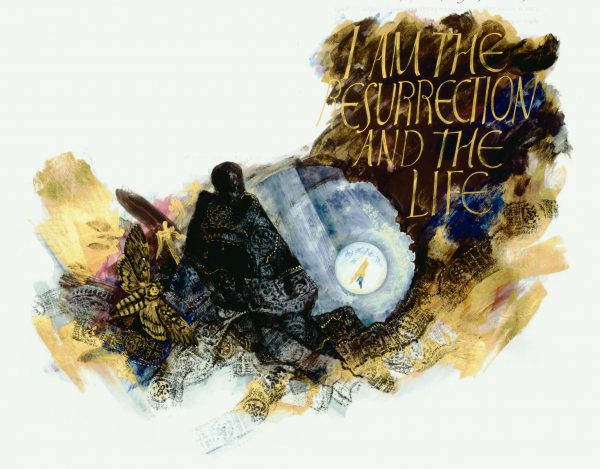

As the border to Birth of Christ, Jackson employs a textile pattern used only also in Raising of Lazarus. In this illumination, the viewer looks from the perspective of Lazarus inside the tomb, rather than the crowd outside the tomb. We are Lazarus, seeking resurrection.

Lazarus sits up and moves toward the light at the end of the tunnel, symbolizing Jackson’s mother’s near-death experience when giving birth to him.vii By connecting his own birth with Lazarus’s new life, Jackson links Jesus’ miracle of raising Lazarus with the miracle of new life worked through women worldwide. The connection between Lazarus’s rebirth and women’s childbirth also evokes Lazarus’s sisters Mary and Martha, who place faith in Jesus by appealing to him for a miracle in saving their brother (John 11:3). Mary was not just a random vessel. Her faith and witness, demonstrated by her canticle and her courage in bearing a baby despite social stigma, make her a prophet and miracle-worker in her own right.

i Amy-Jill Levine, “Gospel of Matthew,” in Women’s Bible Commentary, ed. Carol A. Newsom, Sharon H. Ringe, and Jacqueline E. Lapsley, 3rd ed. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2012), 467.

ii Fraher, “The Illuminated Imagination: Layered Metaphor in The Saint John’s Bible Frontispiece Genealogy of Christ,” 13.

iii Patella, Word and Image, 247.

iv Jane D. Schaberg and Sharon H. Ringe, “Gospel of Luke,” in Women’s Bible Commentary, ed. Carol A. Newsom, Sharon H. Ringe, and Jacqueline E. Lapsley, 3rd ed. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2012), 504.

v N. Clayton Croy and Alice E. Connor, “Mantic Mary? The Virgin Mother as Prophet in Luke 1.26-56 and the Early Church,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 34, no. 3 (2012): 254–76.

vi Ferguson, Signs and Symbols in Christian Art, 151; Laura Kelly Fanucci, “Variation on a Theme: Intertextuality in the Illuminations of the Gospel of Luke,” Obsculta 2, no. 1 (2009): 23. Thanks to Anne Kaese for pointing out the significance of Mary’s red shirt.

vii Patella, Word and Image, 264.